I lost track of how many times I have seen Pan’s Labyrinth while using it as a case study for my Master’s thesis: I watched it at normal speed, on high speed, with commentary, and without; I watched all the DVD extras, then watched them again. After I had defended my thesis, my wife asked me what I wanted to watch. I replied, “One more time, all the way through.” Since then, I’ve viewed it in six different courses as my end-of-term movie (I realize students stop reading several weeks before the end of term, so I prefer to work with that problem, not against it). And when students ask me if I’m tired of watching it, I reply, “No. Every time I watch it, I see something new.”

I’ve met a number of people who cannot imagine someone subjecting themselves to an encore viewing, let alone so many they lose count. These viewers dislike Pan’s Labyrinth for its darkness, for the sorrow and tragedy of its ending. They find the brutality of Captain Vidal abhorrent (and well they should). Like Stephen King, they are terrified by the Pale Man. For many, the film’s darkness overshadows the light; consequently, viewers are often repulsed by it. I love Pan’s Labyrinth for its darkness, sorrow, and brutality. Without those harsh elements the film would be a milquetoast modern fairytale, as tame as The Lady in the Water: a tale of wide-eyed wonder without the wolf.

Fairy tales are often stripped of their darkest and most threatening elements, or transformed into complex morality tales to mirror current values, the victim of an overprotective industry of children’s literature. This is not a new development. To make fairy tales more suitable for young audiences, editors in Victorian England altered the tales, omitting events or elements they deemed too harsh. While many children’s fairy tale collections include a version of Little Red Riding Hood in which the huntsman comes to the rescue before the wolf attacks, the Brothers Grimm’s tale of Little Red Cap describes the “dear little girl whom everyone loved” being “gobbled up” quite suddenly. The wolf eventually meets his demise following an abrupt caesarean section rescue, compounded by a lethal case of massive gall stones courtesy of Little Red Cap, while in another version, Little Red Cap baits the wolf into drowning.

In some modern versions of Little Red Riding Hood, the wolf’s violent demise is replaced by a hasty getaway. Patricia Richards, in an article titled “Don’t Let a Good Scare Frighten You: Choosing and Using Quality Chillers to Promote Reading,” notes that the alteration of the wolf’s fate from execution to evasion is perceived as “less violent and less frightening, but children found it scarier because the threat of the wolf remains unresolved.” Rather than finding gory or horrific details of devoured heroes or drowned villains terrifying, children reported they found “stories with no endings as frightening.”

If ambiguity over the demise of the villain is maintained, then a sense of horror remains. This is a standard trope of the horror movie, utilized for the utilitarian possibility of the money-making sequel, but artistically for a sense of lingering dread. The audience feels a sense of relief when Rachel Keller, the heroine of The Ring seems to have assuaged the vengeance-driven ghost-child Samara; the major-key musical swell tells us they all lived happily-ever-after. This moment is shattered when Rachel returns home to tell her son Aidan all is well, only to have the hollow-eyed Aidan reply, “You weren’t supposed to help her. Don’t you understand, Rachel? She never sleeps.” The ensuing nightmare return of Samara onscreen has become an iconic moment in horror.

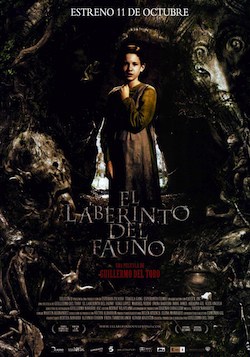

As a director, Guillermo Del Toro is well suited to dealing with horror in his fairy tale; his filmography prior to Pan’s Labyrinth, without exception, depicts a struggle between good and evil, from the subtle and nuanced Devil’s Backbone to the comic book morality of Hellboy, to the monstrous villains of Cronos, Blade II, and Mimic.

Captain Vidal, the wicked stepfather of Pan’s Labyrinth, serves both as the real-world, real-life villain within the film’s ontology of Franco’s Spain, and also the cipher by which the monstrosities of faerie can be understood. The two monsters of Pan’s Labyrinth, the Monstrous Toad and the Pale Man, can be read as expressions of Vidal’s monstrosity, viewed through the childsight lens of Faerie. Ofelia’s entrance into the colossal fig tree inhabited by the Monstrous Toad presents a subtle sexual imagery. The entrance to the tree is shaped like a vaginal opening with its curved branches resembling fallopian tubes, a resemblance which Del Toro himself points out in the DVD commentary. The tree’s sickened state mirrors her pregnant mother’s fragile condition, further manifested by a vision of blood-red tendrils creeping across the page of Ofelia’s magic book. This vision occurs immediately prior to Ofelia’s mother’s collapse due to a complication in the pregnancy, as copious amounts of blood run from between her legs.

The connection between the Tree and Ofelia’s mother is overt, and intentional, on Del Toro’s part. These images are symbolic markers for the sexual union between Ofelia’s mother and Vidal. Vidal is the giant toad, who has entered the tree out of lustful appetites, slowly killing the tree through its “insatiable appetite” for the pill bugs within. Vidal is a subtle Bluebeard—while he does not actively cannibalize Ofelia’s mother, his obsession with a male progeny is effectively her undoing. The tree was once a shelter for the magical creatures of the forest, as Ofelia’s mother once was shelter for her. Ofelia’s tasks can be seen both as trials to secure her return to her Faerie kingdom, as well as reflections of the harsh realities she experiences.

Captain Vidal is Del Toro’s gender reversal of the wicked step mother. Marina Warner notes that in many traditional fairy tales “the good mother dies at the beginning of the story” only to be “supplanted by a monster.” Here, the good father is dead, leaving the beast father to fill the void. From his first moment onscreen Vidal expresses an authoritarian patriarchal presence, exuding a classic machismo partnered with the harsh male violence expressed with multiple visual cues: his immaculate fascist military uniform and a damaged pocket watch, allegedly rescued from the field of battle where Vidal’s dying father smashed it, so his son would know the hour of his violent death in combat; Vidal tells his officers that to die in battle is the only real way for a man to die, as he storms confidently into a hail of rebel bullets. His blind confidence that his unborn child is a son bespeaks his utter patriarchy: when the local doctor asks how Vidal can be so certain that the unborn child is a boy, Vidal places a ban on further discussion or inquiry by replying, “Don’t fuck with me.” His obsession with producing a son is nearly thwarted by his own unrestrained violence when he kills the doctor for assisting a tortured prisoner to die, requiring a troop paramedic to preside over the delivery, ostensibly resulting in his wife’s death. This obsession with a male progeny is the true motivation for Vidal’s sexual union with Ofelia’s mother: his appetite is for food and consumption, rather than for sexual contact. Ofelia’s mother is simply another object to devour, like the Tree; once she is used as a vessel for Vidal’s son, she is no longer of use. When it becomes clear that the delivery has gone mortally wrong, Vidal urges the field medic overseeing the birth to save the child at the expense of the mother’s life.

The Pale man is another symbol of the consuming aspect of Vidal’s nature. This sick, albino creature presides over a rich, bountiful feast, but eats only the blood of innocents. Del Toro’s commentary reveals that the geometry of the Pale Man’s dining room is the same as Vidal’s: a long rectangle with a chimney at the back and the monster at the head of the table. Like the Pale Man, Vidal also dines on the blood of innocents. He cuts the people’s rations, supposedly to hurt the rebels, but eats very well himself; in many scenes he savors his hoarded tobacco with almost sexual ecstasy; but this is not a man with sexual appetites. It is true that he has copulated with Ofelia’s mother, but he is more akin to the Grimm Brothers’ Big Bad Wolf, who wishes to eat Little Red Riding Hood, than the wolf of “The Story of Grandmother” who invites the girl to strip before coming to his bed. Vidal is the sort of wolf James McGlathery describes, one who is neither “a prospective suitor, nor even clearly a seducer of maidens as one usually thinks of the matter. His lust for Red Riding Hood’s body is portrayed as gluttony, pure and simple.” The conflation of consumption, of food, tobacco, and drink, as Vidal’s passion throughout the film underscores this idea. This gluttonous obsession proves Vidal’s undoing: in a wonderful use of foreshadowing, Ofelia kills the Monstrous Toad by tricking it into eating magic, disguising them as the pill bugs the monster lives on. This mirrors the end of the film, when Ofelia renders Captain Vidal nearly unconscious by lacing his liquor glass with her deceased mother’s medication, tricking him into drinking it.

These monsters are clearly Vidal’s avatars in Faerie. All of the monsters in Pan’s Labyrinth are blatantly evil, without remorse for their actions. All act from unrestrained appetite: the frog devouring the tree, the Pale Man dining upon the blood of innocents (his skin hangs in flaps, implying that he had once been much larger), and Vidal sucking the vitality out of the people around him. The first two are monstrous in their physical aspect; the Pale Man is especially frightening as he pursues Ofelia down his subterranean corridors, hand stretched in longing, pierced with ocular stigmata, “the better to see you with.” Vidal by comparison is handsome and well-manicured, meticulously grooming himself each morning, never appearing in the presence of his subjects as anything less than the perfectly arrayed military man. His monstrosity is internal, although Mercedes’ mutilation of his face renders it more external for the film’s climactic scenes. An attentive viewer will also note further foreshadowing in the similarity of the Pale Man’s staggering gait and outstretched hand, and Vidal’s drugged pursuit of Ofelia with arm outstretched to aim his pistol.

Vidal’s external brutality proves to be the most horrific in the film, eclipsing any terror either the Monstrous Toad or Pale Man could conjure. Friends avoided seeing the movie based only on descriptions of Vidal bashing in a peasant’s face with a bottle, or performing torture on a captured rebel, (This second atrocity is performed offscreen; the audience only sees the result of Vidal’s labors). “You can either make it spectacle or dramatic,” says Del Toro in the director’s commentary. In film, a cut on the cheek or on the temple has become commonplace enough that it doesn’t even register for the average filmgoer. The mutilation of Vidal’s face by Mercedes, the rebel-sympathizing housekeeper and surrogate caretaker of Ofelia, is the sort of violence that “immediately elicits a reaction.” Del Toro deliberately designed the hyperbolic violence of Pan’s Labyrinth to be “off-putting, rather than spectacular … very harrowing … designed to have an emotional impact.” The only time Del Toro utilizes violence for spectacle is in the scene where the Captain sews his mutilated cheek back together. The camera never turns away from the spectacle of the Captain driving in the needle and pulling it through, over and over, to illustrate how relentless a monster Vidal is: like the Big Bad Wolf (or the Terminator) he will not stop until he is killed.

If the Big Bad Wolf must die to make the horror a fairy tale, so too must Captain Vidal. While the Captain is an imposing onscreen threat, there is no question as to the ultimate outcome. The villain cannot simply die, for the violence must be hyperbolic: the monstrous toad explodes; the Pale Man is left to starve in his lair. Mercedes’ reply to Vidal’s request that his son be told the time and place of his death is, “He will never even know your name.” At the end, the Captain is not merely killed; he is obliterated. Vidal and his avatars receive their “just reward,” as dictated by the tradition of the fairy tale.

To have toned down Vidal and his monstrous twins would be to tone down the layers of menace. Real or imagined, Ofelia’s actions would lose their significance: her rebellious spirit would be nothing more than adolescent acting-out, a temper tantrum rendered fantastic. However, it is the double-resistance of both Ofelia and the rebels in the hills that provide the thematic thrust of Pan’s Labyrinth, the resistance of Fascism in all its forms. Discussion of this film often centers on whether or not Ofelia’s quests into the realm of Faerie are real. Those who conclude she has imagined them conclude her victory is an empty, illusory one.

This misses the point entirely.

Real or imagined, Vidal and his avatars are symbols of Fascism, of unrestrained oppression. Ofelia and the rebels in the hills exist to resist. In the smallest action of refusing to call Vidal her father, to the life-risking act of kidnapping her infant brother, Ofelia displays a refusal to be cowed in the face of monstrous evil. This is what Del Toro is concerned with, and it is why his villains are so monstrous. In the world of Pan’s Labyrinth, disobedience is a virtue: when Vidal learns of the Doctor’s betrayal, he is confounded, unable to understand the Doctor’s action. After all, he is the monstrous Vidal. The Doctor knows this man’s reputation—he must realize the consequence of his action. And yet, he calmly replies, “But Captain, to obey – just like that – for obedience’s sake… without questioning… That’s something only people like you do.” And to disobey, to resist the monster, is something only people like Ofelia, Mercedes, and the rebels do. To have them defy anything but a true monster would cheapen their resistance. And this is why, despite the difficulty in witnessing the darkness, the sorrow, and the brutality of Pan’s Labyrinth, I would never trade the Big Bad Wolf of Captain Vidal for the toothless lawn-dogs of Lady in the Water.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.